How Pedro Albizu Campos

Got a Bad Deal

(September 12, 1891 – April 21, 1965)

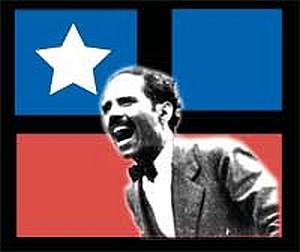

Pedro Albizu

Campos was

a Puerto Rican attorney and politician, and the leading figure in the Puerto

Rican independence movement. Gifted in languages, he spoke six; graduating from

Harvard Law School with the highest grade point average in his law class, an

achievement that earned him the right to give the valedictorian speech at his

graduation ceremony.

Pedro Albizu

Campos was

a Puerto Rican attorney and politician, and the leading figure in the Puerto

Rican independence movement. Gifted in languages, he spoke six; graduating from

Harvard Law School with the highest grade point average in his law class, an

achievement that earned him the right to give the valedictorian speech at his

graduation ceremony.

However, hostility towards his mixed racial heritage would lead to his professors

delaying two of his final exams in order to keep him from graduating

on time. During his time at Harvard University he became involved in the Irish

struggle for independence.

Albizu Campos was the president and spokesperson of the Puerto Rican Nationalist

Party from 1930 until his death in 1965. Because of his oratorical skill, he was

hailed as El Maestro (The Teacher). He was imprisoned twenty-six years for

attempting to overthrow the United States government in Puerto Rico. In 1950, he

planned and called for armed uprisings in several cities in Puerto Rico on

behalf of independence. Afterward he was convicted and imprisoned again. He died

in 1965 shortly after his pardon and release from federal prison, some time

after suffering a stroke. There is controversy over his medical treatment in

prison.

He was born in a sector of Barrio Machuelo Abajo in Ponce, Puerto Rico to Juana

Campos, a domestic worker of Spanish, African and Taíno ancestry, on 12th.

of

September of 1891. His father, Alejandro Albizu Romero, known as "El Vizcaíno," was

a Basque merchant, from a family of Spanish immigrants who had temporarily

resided in Venezuela. From an educated family, Albizu was the nephew of the

danza composer Juan Morel Campos, and cousin of Puerto Rican educator Dr. Carlos

Albizu Miranda. The boy's mother died when he was young and his father did not

acknowledge him until he was at Harvard University.

Albizu graduated from Ponce High School, a "public school for the

city's white elite." In 1912, Albizu was awarded a scholarship to study

Engineering, specializing in Chemistry, at the University of Vermont. In 1913,

he transferred to Harvard University so as to continue his studies.

At the outbreak of World War I, he volunteered in the United States Infantry.

Albizu was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Army Reserves and sent to the

City of Ponce, where he organized the town's Home Guard. He was called to serve

in the regular Army and sent to Camp Las Casas for further training. Upon

completing the training, he was assigned to the 375th Infantry Regiment. The

United States Army, then segregated, assigned Puerto Ricans of recognizably

African descent as soldiers to the all-black units, such as the 375th Regiment.

Officers were men classified as white, as was Albizu Campos.

Lieutenant Pedro Albizu Campos was honorably discharged from the Army in 1919,

with the rank of First Lieutenant. However, his exposure to racism during his

time in the U.S. military altered his perspective on U.S.- Puerto Rico

relations, and he became the leading advocate for Puerto Rican independence.

Albizu graduated from Harvard Law School in 1921 while simultaneously studying

Literature, Philosophy, Chemical Engineering, and Military Science at Harvard

College. He was fluent in six modern and two classical languages: English,

Spanish, French, German, Portuguese, Italian, Latin, and ancient Greek.

Upon

graduation from law school, he was recruited for prestigious

positions, including a law clerkship to the U.S. Supreme Court, a diplomatic

post with the U.S. State Department, the regional vice-presidency (Caribbean

region) of a U.S. agricultural syndicate, and a tenured faculty appointment to

the University of Puerto Rico.

So What Happened?

— The Bad Deal —

On June 23, 1921, after graduating from Harvard Law School, he returned to

Puerto Rico—but without his law diploma. He had been the victim of racial

discrimination by one of his professors, who delayed Albizu Campos' third-year

final exams for courses in Evidence and Corporations. He was about to

graduate with the highest grade-point average in his entire law school class. As

such, he was scheduled to give the valedictory speech during the graduation

ceremonies. His professor delayed his exams so that he could not complete his

work, and avoided the "embarrassment" of a Puerto Rican law valedictorian.

Nationalist activists wanted independence from foreign banks, absentee

plantation owners, and United States colonial rule. Accordingly, they started

organizing in Puerto Rico. In 1919, José Coll y Cuchí, a member of the Union

Party of Puerto Rico, took followers with him to form the Nationalist

Association of Puerto Rico in San Juan, to work for independence. They gained

legislative approval to repatriate the remains of Ramón Emeterio Betances, the

Puerto Rican patriot, from Paris, France.

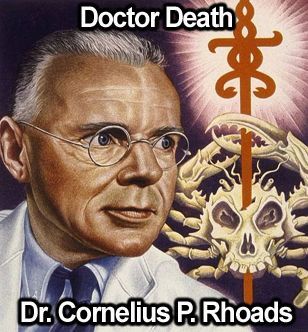

In 1932, Albizu published a letter accusing Dr. Cornelius P. Rhoads, an American

pathologist with the Rockefeller Institute, of killing Puerto Rican patients in

San Juan's Presbyterian Hospital, as part of his medical research. Albizu Campos

had been given an unmailed letter by Rhoads addressed to a colleague, found

after Rhoads returned to the United States.

Part of what Rhoads wrote, in a letter to his friend which began by complaining

about another's job appointment, included the following:

"I can get a damn fine job here and

am tempted to take it. It would be ideal except for the

Puerto Ricans. They are beyond doubt the dirtiest,

laziest, most degenerate and thievish race of men ever

inhabiting this sphere. It makes you sick to inhabit the

same island with them.

"I can get a damn fine job here and

am tempted to take it. It would be ideal except for the

Puerto Ricans. They are beyond doubt the dirtiest,

laziest, most degenerate and thievish race of men ever

inhabiting this sphere. It makes you sick to inhabit the

same island with them.

They are even lower than

Italians. What the island needs is not public health

work but a tidal wave or something to totally

exterminate the population. It might then be livable.

I have done my best to further the process of

extermination by killing off 8 and transplanting cancer

into several more. The latter has not resulted in any

fatalities so far...

The matter of consideration for the

patients' welfare plays no role here - in fact all

physicians take delight in the abuse and torture of the

unfortunate subjects."

Albizu sent copies of the letter to the League of Nations, the Pan American

Union, the American Civil Liberties Union, newspapers, embassies, and the

Vatican. He also sent copies of the Rhoads letter to the media, and

published his own letter in the Porto Rico Progress. He used it as an

opportunity to attack United States imperialism, writing:

"The mercantile monopoly is backed by the financial monopoly... The United

States have mortgaged the country to their own financial interests. The military

intervention destroyed agriculture. It changed the country into a huge sugar

plantation..."

"The mercantile monopoly is backed by the financial monopoly... The United

States have mortgaged the country to their own financial interests. The military

intervention destroyed agriculture. It changed the country into a huge sugar

plantation..."

Albizu Campos accused Rhoads and the United States of trying to

exterminate the native population, saying, "Evidently, submissive people coming

under the North American empire, under the shadow of its flag, are taken ill and

die.

The facts confirm absolutely a system of extermination." He went on, "It

(the Rockefeller Foundation) has in fact been working out a plan to exterminate

our people by inoculating patients unfortunate enough to go to them with virus

of incurable diseases such as cancer."

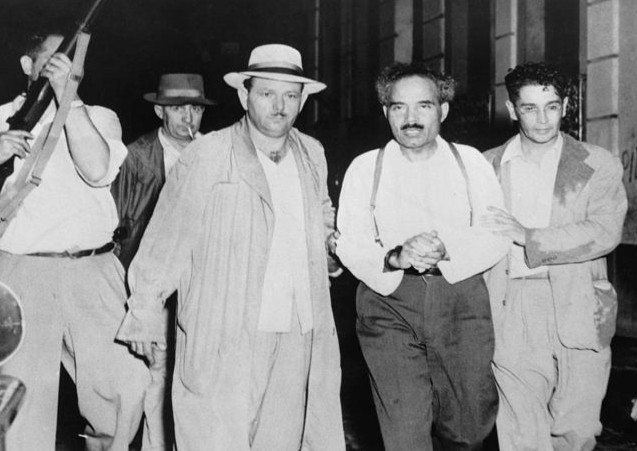

After these events, on April 3, 1936, a federal grand jury submitted an

indictment against Albizu Campos, Juan Antonio Corretjer, Luis F. Velázquez,

Clemente Soto Vélez and the following members of the cadets: Erasmo Velázquez,

Julio H. Velázquez, Rafael Ortiz Pacheco, Juan Gallardo Santiago, and Pablo

Rosado Ortiz. They were charged with sedition and other violations of Title 18

of the United States Code.

Lolita Lebrón called him "Puerto Rico's most visionary leader"

and nationalists consider him "one of the island's greatest patriots of the 20th

century." Juan Manuel Carrión

wrote that "Albizu still represents a forceful challenge to the very fabric of

Puerto Rico's colonial political order."

His followers state that Albizu's

political and military actions served as a primer for positive change in Puerto

Rico, including the improvement of labor conditions for peasants and workers, a

more accurate assessment of the colonial relationship between Puerto Rico and

the United States, and an awareness by the political establishment in

Washington, D.C. of this colonial relationship.

Supporters state that the legacy is that of an exemplary sacrifice for the

building of the Puerto Rican nation...a legacy of resistance to colonial rule. His critics say that he "failed to attract and offer concrete

solutions to the struggling poor and working class people and thus was unable to

spread the revolution to the masses."

The revival of public observance of the Grito de Lares and its significant icons

was a result of Albizu Campos's efforts as the leader of the Puerto Rican

Nationalist Party.

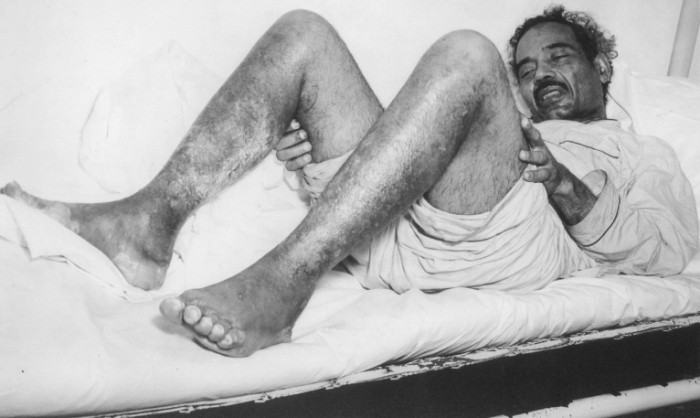

During his imprisonment, Albizu suffered deteriorating health. He alleged that

he was the subject of human radiation experiments in prison and said that he

could see colored rays bombarding him. When he wrapped wet towels around his

head in order to shield himself from the radiation, the prison guards ridiculed

him as El Rey de las Toallas (The King of the Towels).

Officials suggested that Pedro Albizu Campos was suffering from mental illness,

but other prisoners at La Princesa prison including Francisco Matos Paoli,

Roberto Díaz and Juan Jaca, claimed that they felt the effects of radiation on

their own bodies as well.

Dr. Orlando Daumy, a radiologist and president of the Cuban Cancer Association,

traveled to Puerto Rico to examine him. From his direct physical examination of

Albizu Campos, Dr. Daumy reached three specific conclusions:

1) that the sores on Albizu Campos were

produced by radiation burns

2) that his symptoms corresponded to those of a person

who had received intense radiation,

3) that wrapping himself in wet towels was the best way

to diminish the intensity of the rays.

In 1956, Albizu suffered a stroke in prison and was transferred to San Juan's

Presbyterian Hospital under police guard.

On November 15, 1964, on the brink of death, Pedro Albizu Campos was pardoned by

Governor Luis Muñoz Marín. He died on April 21, 1965. More than 75,000 Puerto

Ricans were part of a procession that accompanied his body for burial in the Old

San Juan Cemetery.

Statue of Don Pedro Albizu Campos in Mayaguez

donjibaro@gmail.com

“Live in such a way that no one blames the rest of us

nor finds fault with our work.” —(2 Corinthians 6:3)

Jibaros.Com®,

Jibaros.Net® - ALL content is Copyright © by Orlando Vázquez,

owner-designer and com does not accept any responsibility for the

privacy policy of third party sites